The world is rapidly shifting toward renewable energy solutions as the urgency of climate change grows. Solar energy is a cornerstone of that transition: it uses sunlight — a virtually limitless source — to produce electricity with minimal on-site pollution or direct greenhouse gas emissions. At the same time, a complete view of the environmental impact of solar energy requires examining manufacturing, materials sourcing, and end-of-life handling.

Assessing solar energy sustainability means looking at the full lifecycle. Solar panels commonly carry warranties and are expected to operate for 25–30 years, while many systems repay their embodied energy within roughly 1–4 years depending on technology and location (see lifecycle and LCA studies for specifics). That said, production involves mining metals and glass, and recycling PV cells is becoming increasingly important as new regulations and innovations in sustainable energy technology emerge to reduce waste and recover materials.

We should celebrate the benefits of solar power — lower operating costs for businesses and homeowners, reduced electricity-sector emissions, and more resilient local energy — but not overlook challenges such as material extraction, hazardous substances in some technologies, and end-of-life management. Progress in manufacturing practices, recycling infrastructure, and policy incentives is helping address these issues.

Federal incentives like the investment tax credit and research by organizations such as the Solar Energy Technologies Office (SETO) and the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) support cleaner production methods and broader deployment; the EIA also tracks environmental effects and deployment trends (see EIA analysis).

Key Takeaways

- Solar generates electricity with little operational pollution, making it an important clean energy solution.

- Manufacturing and materials sourcing create environmental impacts that must be managed through better practices and recycling.

- Proper end-of-life planning for panels is critical to long-term sustainability.

- Policies, incentives, and R&D are accelerating more sustainable production and wider adoption.

- Balancing benefits and impacts will let solar play a central role in climate change solutions.

Read on to learn about lifecycle impacts, technology improvements, and practical solutions for sustainable solar deployment.

The Fundamentals of Solar Energy as a Sustainable Source

At its core, solar energy converts sunlight into usable electricity using photovoltaic (PV) systems. PV modules—commonly called solar panels—use semiconductor materials (most often silicon) to capture photons from the sun and generate an electric current. This clean energy source is a major contributor to renewable energy growth and helps reduce reliance on fossil fuels.

Understanding How Solar Panels Convert Sunlight into Electricity

The photovoltaic effect, first observed in 1839 by Alexandre-Edmond Becquerel, is the physical process behind solar electricity: photons hitting a semiconductor material free electrons, producing direct current (DC). In a typical rooftop system, panels are wired to an inverter that converts DC to alternating current (AC) for household use or grid export.

Example: a typical 6 kW residential rooftop PV system in a sunny U.S. region can produce roughly 7,000–9,000 kWh per year depending on local sun exposure (insolation) and system orientation — enough to cover most household electricity needs in many areas.

The Role of Photovoltaic (PV) Systems in Sustainable Energy

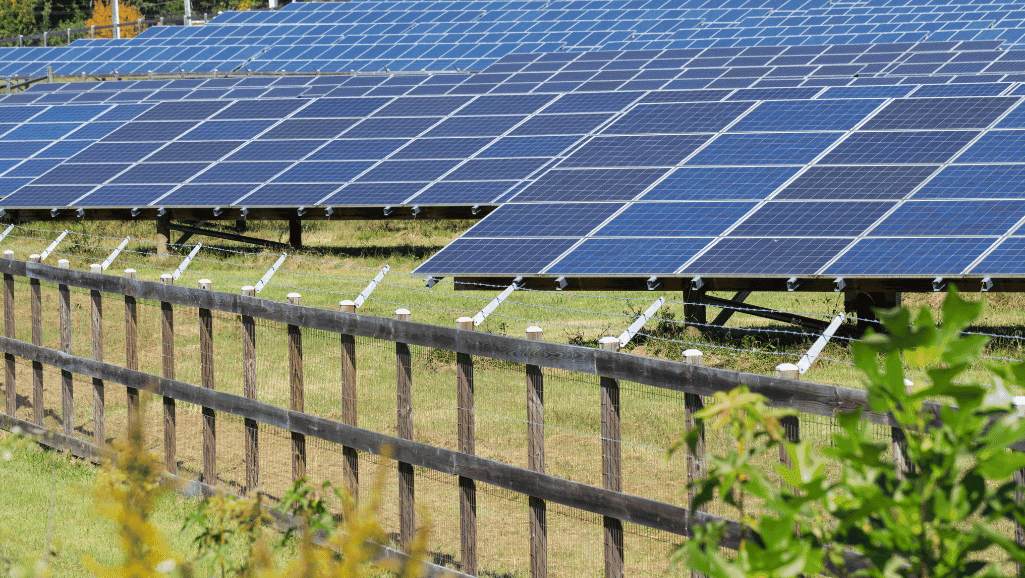

Photovoltaic systems reduce demand for fossil-fuel generation and associated emissions by supplying clean electricity at the point of use or to the grid. Advances in PV technology—such as bifacial panels that collect light on both sides and concentrated PV that uses optics to focus sunlight—improve energy yield. Large-scale solar farms and distributed rooftop systems together enable flexible, scalable clean energy deployment.

As PV systems and related technologies evolve, their improved efficiency and lower costs continue to expand solar energy’s role as a practical, scalable source of electricity from the sun. For detailed technical background and performance data, see NREL and EIA resources on how PV systems work.

Environmental Benefits of Solar Power

Solar power is a leading clean energy source that reduces reliance on fossil fuels and helps lower greenhouse gas emissions from the electricity sector. When solar replaces generation from coal or natural gas, it avoids carbon dioxide and methane emissions that drive climate change. Life-cycle analyses typically show that utility-scale solar systems emit far less CO2 per megawatt-hour than fossil-fuel plants (see NREL and EPA studies for regional values).

Solar PV also uses far less water in operation than thermoelectric power plants. Photovoltaic panels require minimal cooling water; most water use is associated with occasional washing and manufacturing. Compared with coal or nuclear plants — which use hundreds to thousands of gallons per MWh for cooling — PV’s operational water intensity is much lower, making solar a strong choice for water-constrained regions.

- Lower emissions: Solar power displaces fossil generation, reducing carbon and other air pollutants per MWh produced.

- Conservation of water resources: PV’s operational water needs are minimal compared with many conventional power sources.

- Technological progress: Improvements in module design and materials have increased energy yields and reduced material intensity per watt produced.

Module and system efficiency have improved steadily. For example, commercial rooftop modules commonly exceed 20% module efficiency in recent years, while ongoing research and manufacture improvements continue to raise practical yields and lower costs. Those gains make solar’s environmental benefits more accessible to homeowners, businesses, and grid operators alike.

Overall, solar energy offers clear environmental benefits — lower greenhouse gas emissions, reduced water use, and rapidly improving technology — though the full net benefit depends on siting, manufacturing practices, and end-of-life management.

Energy Payback from Solar Systems

The concept of energy payback (EPBT) is central to assessing how solar PV systems contribute to cleaner energy. EPBT measures how long a system must operate to generate the same amount of energy that was consumed during its manufacture, transport, and installation. Shorter payback times mean the system becomes a net producer of clean energy sooner.

Advances in module manufacturing, higher module efficiency, and improved balance-of-system components have steadily reduced embodied energy. Meanwhile, longer warranties and better performance monitoring have improved expected operational lifetimes, strengthening solar energy’s case as a low-impact energy source (see lifecycle overview).

Assessing the Lifecycle of Solar Panels and Energy Production

Typical energy payback times depend on technology and location. Many multicrystalline (or polycrystalline) silicon modules historically have EPBTs in the range of about 3–5 years, while some thin-film technologies can have payback times around 2–4 years, varying with sunlight (insolation) at the installation site and manufacturing methods. Higher irradiation sites and more efficient systems shorten EPBT.

As manufacturing and module efficiency improve, projected EPBTs move lower — for example, improvements in manufacturing energy intensity and higher module output could reduce EPBT in many cases by a year or more compared with older systems. Exact projections depend on technology, region, and supply-chain factors.

The Lifespan of PV Systems and Operational Sustainability

After a system reaches EPBT, it continues to produce largely low-carbon electricity for the remainder of its life. Most PV systems are designed to last 25–30 years or more, with many performance warranties guaranteeing a percentage of initial output over that period. Over multi-decade lifetimes, a rooftop or utility PV system typically offsets many times the embodied energy and avoids substantial greenhouse gas emissions compared with fossil-generation alternatives.

| System TypeCurrent Energy Payback (Years)Anticipated Energy Payback (Years)Emissions Avoided (Tons CO2) | |||

| Multicrystalline-Silicon | 4 | 2 | 100 |

| Thin-Film | 3 | 1 | 100 |

Table notes: the values above illustrate typical ranges and improvement targets; EPBT and avoided-emissions estimates vary by location, system size, lifetime assumptions, and grid carbon intensity. For a simple worked example: a 5 kW rooftop system in a high-sun U.S. location producing ~7,500 kWh/year could repay embodied energy within ~2–4 years and then deliver two-plus decades of low-carbon energy, avoiding several tons of CO2 annually compared with coal-fired generation. See NREL and peer-reviewed LCA studies for detailed methodologies and regional figures.

Is solar energy sustainable: Analyzing the Materials and Production

The rapid growth in solar energy production raises important questions about sustainability beyond a panel’s operating life. To judge net environmental impact, we must examine raw-material extraction, manufacturing energy and emissions, use of hazardous substances in certain technologies, and end-of-life management including recycling.

Environmental Costs of Material Extraction and Manufacturing

Common PV modules use silicon (refined from quartz) and small amounts of silver, aluminum, copper, and other metals. Mining and refining those materials consume energy and can affect local ecosystems through land disturbance and water use. Life-cycle assessments (LCAs) show that embodied energy and upstream emissions vary widely by material source and manufacturing location, so cleaner supply chains and lower-energy fabrication reduce overall impacts.

Handling Hazardous Chemicals Used in PV Cell Manufacturing

Not all PV technologies use the same materials: cadmium is a component of cadmium telluride (CdTe) thin-film modules, while some older or specialty cells have used lead in solder. These substances pose risks if improperly handled, so manufacturers and regulators follow strict controls for worker safety, emissions, and waste. Clear labeling, contained manufacturing processes, and proper disposal or recycling at end-of-life limit environmental and health risks.

Solar Panels End-of-Life: Recycling and Waste Management

As installations age, end-of-life management becomes critical. Recycling recovers glass, aluminum frames, and valuable semiconductors (silicon, silver, indium in some panels), reducing the need for virgin materials and lowering life-cycle emissions. Forecasts—based on current deployment trajectories—anticipate large cumulative volume of decommissioned panels by 2050, which makes building recycling capacity essential. Policy drivers such as EU WEEE rules and emerging state-level requirements in the U.S. are starting to shape industry responses.

Practical recycling approaches range from mechanical separation (recovering glass and aluminum) to chemical processes that reclaim silicon and metals. Current commercial recycling rates vary by region and technology, and continued investment in economically viable recycling methods will be key to keeping solar energy sustainable as production scales.

Understanding how PV systems move from raw materials through manufacturing to recycling highlights opportunities to cut emissions and waste across the supply chain. Stronger materials sourcing standards, improved manufacturing efficiency, and robust recycling programs will help ensure solar energy’s environmental benefits continue to grow.

Impacts of Solar Energy on Wildlife and Ecosystems

Expanding solar energy reduces dependence on fossil fuels and cuts greenhouse gas emissions, but large-scale deployments can affect wildlife and ecosystems if not sited and managed carefully. Understanding these impacts enables planners to balance energy production with biodiversity protection.

Large ground-mounted solar farms can cause habitat loss and fragmentation when built on undeveloped land. Species with limited ranges — for example, desert tortoises in parts of the U.S. Southwest or nesting birds in open grasslands — are particularly vulnerable to site conversion and increased human activity. Construction and operation can also change local soil stability and hydrology, potentially increasing erosion or altering vegetation communities.

- Soil and habitat impacts: grading and clearing during construction can compact soil, increase erosion, and reduce native plant cover.

- Disturbance to wildlife: increased human presence, access roads, and lighting can alter animal behavior and predator-prey dynamics.

Mitigation and best practices greatly reduce these risks. Preferred strategies include avoiding intact natural habitats, prioritizing previously disturbed or low-biodiversity lands, and applying adaptive management—monitoring impacts and adjusting operations over time. Physical measures such as non-reflective panels, wildlife-friendly fencing, and bird-diverter devices help reduce direct harm to birds and other animals.

Mitigation best practices

- Site selection: prioritize rooftops, brownfields, degraded agricultural land, and parking-canopy installations over pristine habitats.

- Pre-construction surveys: conduct thorough ecological assessments and seasonal surveys for sensitive species.

- Design measures: use wildlife-friendly fencing, maintain movement corridors, and minimize grading.

- Monitoring and adaptive management: implement post-construction monitoring and modify operations based on findings.

Several monitored projects have demonstrated positive outcomes: for instance, agrivoltaic and pollinator-friendly ground-mount sites have increased plant diversity beneath panels while producing energy, and careful siting has avoided impacts to sensitive species in many DOE- and state-funded programs (see DOE summary studies for examples).

Finally, many impacts can be avoided by favoring distributed installations (rooftop and parking), colocating solar with agriculture, and using degraded lands. With careful planning, technology choices, and ongoing monitoring, solar energy can expand while minimizing harm to wildlife and ecosystems.

For guidance on siting and wildlife mitigation, refer to agency resources such as the DOE/NREL reports and the Solar Impacts on Wildlife and Ecosystems summary linked in planning documents.

Water Usage in Solar Energy Production

Solar energy is an increasingly important source of sustainable power, and understanding its water footprint is essential for protecting local ecosystems. Different solar technologies and operational practices have very different water needs, so planning and design choices matter.

The Need for Water in Cleaning Solar Collectors

Photovoltaic (PV) panels require occasional cleaning to maintain performance, but cleaning water use is generally small compared with cooling needs at thermal plants. Cleaning practices vary by site; routine washing can amount to a few gallons per MWh of electricity produced (estimates depend on climate, soiling rates, and cleaning frequency). Many manufacturers and operators are adopting low-water cleaning methods and automation to cut water use.

Impact of Water Usage by Solar Power Plants on Local Ecosystems

Solar PV systems use minimal water in operation compared with thermoelectric plants. Concentrating solar power (CSP) or solar thermal plants that use steam cycles can have substantially higher water needs for cooling — commonly in the hundreds of gallons per MWh when wet cooling is used. By contrast, PV’s operational water intensity is low, making PV preferable in water-stressed regions.

Common strategies to reduce water impacts include dry or hybrid cooling for thermal plants, using reclaimed water for washing, and siting PV on rooftops or brownfields to avoid stressing local water resources. Floating PV (on reservoirs) can also reduce evaporation while boosting panel performance in some cases.

| Energy SourceTypical Water Usage per MWhNotes | ||

| Solar PV (cleaning) | Low — site-dependent (generally a few gallons/MWh) | Depends on soiling and cleaning method; dry cleaning reduces demand |

| Solar Thermal (CSP, wet cooling) | Hundreds of gallons/MWh | Cooling method and plant design drive wide variation |

| Coal-fired | Hundreds to ~1,100 gallons/MWh | Large water withdrawals for cooling and steam |

| Nuclear | Hundreds of gallons/MWh | High cooling water needs |

| Hydroelectric | Very high (contextual; evaporation over reservoirs) | Evaporation losses depend on reservoir size and climate |

For operators and planners, best practices include adopting dry-cleaning technologies, using reclaimed water where available, choosing low-water cooling for thermal plants, and favoring PV deployment types that minimize additional water demand. See regional guidance and NREL resources for specific numbers and methods to reduce water use in solar projects.

Minimizing Land Use and Promoting Biodiversity

Developing solar energy projects requires careful attention to biodiversity in solar farming and thoughtful site selection. Well-planned projects can support local agriculture and protect native landscapes while delivering renewable energy, but poor siting can harm ecosystems.

Site Selection Best Practices for Solar Installations

Good site selection prioritizes lands with low ecological value: rooftops, parking canopies, brownfields, degraded former industrial sites, and marginal agricultural land. Avoiding intact habitats reduces the risk of habitat loss and fragmentation. Early-stage ecological assessments and permitting reviews identify constraints such as endangered-species habitat, wetlands, or migration corridors.

Site selection checklist (short):

- Prefer previously disturbed sites (brownfields, rooftops, parking lots)

- Complete seasonal ecological surveys for sensitive species

- Avoid high-value native ecosystems and critical habitats

- Assess agricultural compatibility and water/soil impacts

Coexistence of Solar Farms with Agriculture and Native Landscapes

Agrivoltaics — colocating solar projects with agricultural uses — is an established approach that can sustain crop or forage production while generating energy. Examples include pollinator-friendly plantings beneath panels that support bees and other beneficial insects, and shade-tolerant crops that benefit from partial cover. In many regions (for example parts of California’s Central Valley), pilot projects show that careful design can let farming and solar energy coexist without displacing prime farmland.

Other land-management practices that promote biodiversity include planting native vegetation under and around arrays, maintaining hedgerows and wildlife corridors, and limiting grading to preserve soil structure. These measures can increase on-site biodiversity and provide habitat benefits compared with conventional, heavily graded installations.

In short, choosing the right sites and integrating solar with compatible land uses helps both energy production and ecosystem health. Project planners should consult regional guidance and design manuals to implement biodiversity-friendly practices from the earliest planning stages.

Advancements in Solar Technology and Efficiency

The solar energy sector is evolving rapidly. Advances across PV module design, balance-of-system components, and storage are increasing system efficiency, lowering costs, and expanding where and how solar can provide electricity from the sun.

Innovations in PV Efficiency and Performance

There are two important distinctions to make: laboratory records and commercial module performance. Lab-scale tandem cells (for example perovskite/silicon tandems) have achieved record efficiencies approaching higher percentages in controlled settings, while commercially available rooftop and utility modules commonly deliver module efficiencies in the ~20%+ range. These material and cell advances promise higher energy production per unit area, improving overall system economics and reducing embodied energy per kWh.

Commercial technology improvements that boost real-world output include bifacial panels (which collect reflected light from both sides) and single-axis trackers that follow the sun. Trackers can increase annual energy yield by roughly 10–25% depending on site latitude and array design; bifacial gains depend on albedo and mounting but commonly add measurable yield in many configurations.

Improved inverters, racking, and system design also raise effective efficiency. Meanwhile, advances in battery storage are enabling greater firming of solar power so systems can supply electricity during evening hours or cloudy periods. Falling battery costs make paired PV-plus-storage systems increasingly feasible for homes, businesses, and grid-scale projects.

Trends in Clean Energy Technology and Green Energy Initiatives

Emerging deployment trends include building-integrated photovoltaics (solar windows and solar tiles) for urban sites, floating PV on reservoirs to reduce land use and sometimes boost panel cooling and performance, and agrivoltaics where solar coexists with agriculture. Floating arrays can sometimes increase energy production modestly (studies show site-dependent uplifts, often cited around ~5–15%) due to panel cooling and reduced soiling.

Artificial intelligence and advanced monitoring systems help optimize operations and predict maintenance, increasing energy production and reliability. Thin-film technologies remain important where weight, flexibility, or lower manufacturing cost are priorities; their commercial competitiveness depends on module lifecycle performance and local project economics.

Taken together, these technologies and system-level solutions are widening solar’s role as a scalable renewable energy source. For project developers and policymakers, the key is distinguishing lab records from commercially deployable technologies and matching innovations to site conditions, demand profiles, and long-term production goals.

Regulatory Framework and Environmental Policies

Understanding the regulatory framework and environmental policies is essential for deploying and managing solar energy systems responsibly. Federal incentives, state rules, and agency research together shape how solar projects are sited, financed, and maintained — including considerations for disposal and recycling at end-of-life.

U.S. Environmental Laws Governing Solar Energy Use and Disposal

Key U.S. policies encourage solar deployment and help manage environmental impacts. The Federal Investment Tax Credit (ITC) provides a tax credit (not a deduction) for a portion of qualified solar installation costs, lowering upfront costs for homeowners and businesses; details and eligibility depend on project type and current law. Other tax provisions such as Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS) depreciation provide accelerated tax depreciation for commercial projects, improving project economics.

PURPA (the Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act) historically required utilities to purchase power from qualifying small renewable generators and helped spur early renewable energy growth; its implementation varies by state and has evolved over time. State-level policies — such as net metering, renewable portfolio standards, and solar renewable energy credits (SRECs) — further affect project viability and how solar power integrates with the grid.

Efforts from SETO and NREL in Managing Solar Energy’s Environmental Impact

Federal research programs play a central role in reducing the environmental footprint of solar energy. The Solar Energy Technologies Office (SETO) and the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) fund R&D to lower costs, improve system durability and recyclability, and reduce embodied energy in manufacturing. SETO’s research priorities include making solar more affordable and resilient; many programs aim to accelerate cost and performance improvements through the 2020s and toward 2030 targets.

These agencies also support work on end-of-life strategies, recycling technologies, and materials-sourcing standards that reduce lifecycle impacts. Combined federal and state incentives, plus R&D, help shift deployment toward lower-cost, lower-impact projects.

| PolicyDescriptionImpact | ||

| ITC | Federal tax credit for qualified solar installations (reduces tax liability) | Lowers upfront costs, encourages residential and commercial adoption |

| MACRS | Accelerated depreciation for commercial solar equipment | Improves project cash flows and investment returns |

| PURPA | Requires utilities to consider purchases from qualifying generators (historical) | Helped stimulate early renewable project growth; state implementation varies |

| SETO R&D | Federal research programs to improve affordability and sustainability | Targets cost reductions and environmental-impact mitigation through innovation |

What this means for homeowners, businesses, and projects: incentives like the ITC can materially reduce installation costs for residential and commercial systems; developers should track state rules (net metering, interconnection, and recycling requirements) that affect project returns and environmental compliance. For precise eligibility, timelines, and application steps, consult IRS guidance, state energy offices, and DOE/SETO resources.

Conclusion

Reviewing solar energy sustainability shows clear environmental and economic benefits: improvements in panel efficiency and falling installation costs have made solar a leading clean energy option. The solar industry also supports a large workforce in the United States; for example, the U.S. solar workforce numbered in the low hundreds of thousands in recent BLS and industry reports — check the latest Department of Energy or Bureau of Labor Statistics releases for current figures and company counts.

Solar panels typically have expected operational lifetimes of about 25–30 years under normal conditions, with many manufacturers offering performance warranties for that range. Over these decades, properly sited PV systems deliver low-carbon electricity and help reduce reliance on fossil fuels.

On a sector level, increasing solar deployment reduces greenhouse gas emissions from electricity production by displacing higher-carbon generation — the exact percentage depends on the grid mix and scale of deployment. Agencies such as the EPA and NREL publish regional and national estimates of avoided emissions and the contribution of solar to decarbonization.

Solar power also delivers practical benefits for communities: it lowers electricity costs for many homeowners and businesses, supports energy access in remote areas, and reduces local air pollution and water use compared with many conventional energy sources. To maximize these benefits while minimizing impacts, projects should follow best practices for siting, materials sourcing, recycling, and community engagement.

Key takeaways:

- Solar energy provides substantial clean energy and carbon-reduction benefits when deployed with attention to lifecycle impacts.

- Panels generally last 25–30 years and commonly repay embodied energy within a few years, after which they deliver mostly low-carbon electricity.

- Managing materials, recycling, water use, and site impacts keeps solar’s net environmental footprint low as production scales.

- Policy incentives, R&D, and industry standards are making solar more affordable and sustainable for homeowners, businesses, and projects.

If you’re considering solar for your home or business, start by checking federal and state incentives, get a site assessment from a reputable installer, and ask about panel warranties and end-of-life plans. For further reading, consult resources from NREL, the EPA, and your state energy office for the latest data and guidance.