The sun supplies a vast, reliable source of power, and clear solar energy information helps people use it effectively. By converting sunlight into usable electricity, solar power is a practical, measurable step toward cleaner energy today and over the coming years.

Every kilowatt-hour of sunlight captured by rooftop or utility-scale panels reduces reliance on fossil fuels and supports local energy resilience. Below are the main, evidence-based takeaways readers should know about how solar energy impacts homes, communities, and the broader energy mix.

Key Takeaways

- Solar panel efficiency continues to improve; many modern modules achieve conversion rates in the low- to mid-20% range (manufacturer specs vary, verify specific model data).

- Properly sized rooftop systems paired with net metering or battery storage can reduce household electricity bills substantially—even to near zero for well-matched systems in sunny regions.

- Installing solar systems often increases home resale value; studies show typical gains that can reach several thousand dollars depending on market and system size.

- Replacing fossil-fuel electricity with solar energy reduces carbon emissions per kWh generated, helping jurisdictions meet climate targets.

- Advances in materials and manufacturing are lowering the upfront cost of solar power and improving access.

- Adoption is growing: more people and homes are adding panels each year, expanding distributed clean power generation.

- Policy moves—such as changes to import tariffs, tax credits, and incentive programs—significantly influence deployment and reflect growing public and governmental support for renewable energy (check current policy status locally).

The Definition and Importance of Solar Energy

Understanding the definition of solar energy clarifies why it is a core component of a sustainable energy transition. Solar energy converts sunlight into electricity and heat through technologies such as photovoltaics (PV) and concentrated solar power (CSP), helping reduce reliance on fossil fuels and supporting cleaner air and lower emissions.

Understanding Solar Energy

Solar energy is harvested in two primary ways: PV systems convert sunlight directly into electricity using semiconductor cells, while CSP uses concentrated sunlight to produce heat that drives turbines or thermal storage. While the sun delivers an enormous amount of energy to Earth—often summarized as “enough sunlight in one hour to meet global annual demand” as a rough illustration—be sure to note that this is a high-level comparison and depends on conversion and collection efficiencies.

Why Solar Energy Is Crucial for Sustainability

Solar power supports sustainability by producing low‑carbon electricity at the point of use or on utility scales, reducing greenhouse gas emissions and import dependence. Solar panel deployments also deliver long-term environmental and economic benefits—lower operational emissions, reduced water use compared with many thermal power plants, and local economic activity tied to installations and maintenance.

Key comparative facts (approximate; see sources for context and methodology):

| Solar Energy FactDetail | |

| Total solar irradiance available to Earth | Vastly exceeds current global energy consumption (illustrative comparisons often use hourly solar irradiance vs. annual demand; conversion losses apply) |

| Conversion efficiency (typical ranges) | Commercial PV modules commonly convert ~15%–23% of sunlight to electricity; solar thermal collectors and concentrated systems vary widely depending on design (hence broader ranges) |

| Land/area considerations | Utility-scale PV systems require land or rooftop area; design choices (bifacial panels, agrivoltaics) can improve land productivity |

| Water use | PV systems use very little water in operation compared with many thermal power plants; CSP with steam cycles can require more water unless dry-cooling is used |

| Typical panel lifespan | Modern panels are designed for ~25 years or more; warranties often guarantee a percentage of rated output over that period |

| Property value impact | Studies indicate solar installations can increase home resale value by several thousand dollars on average, varying by market and system size |

These points show how solar energy technologies can reduce emissions, conserve water, and provide flexible deployment across rooftops and open areas—making them a practical tool for sustainable development when matched with appropriate planning and policy.

Demystifying How Solar Panels Operate

Understanding how solar energy work is essential as more homes and businesses adopt renewable energy. Solar panels capture sunlight and convert it into usable electricity with relatively simple physics and components. Below is a clear, practical walkthrough of the photovoltaic process and the system elements that deliver power to your home or grid.

From Sunlight to Electricity: The Photovoltaic Process

Solar panels are made up of many photovoltaic cells, typically silicon-based semiconductors. When sunlight strikes these cells, photons transfer energy to electrons, freeing them and creating an electric current. That initial flow is direct current (DC) electricity.

An inverter converts DC into alternating current (AC), the form of electricity used by most household appliances and the grid. Modern inverters also provide safety features and system monitoring, and conversion efficiency (DC→AC) typically ranges from about 95% to 99% depending on the inverter type and conditions.

Improvements in Solar Panel Efficiency Over Time

Solar energy technologies have steadily improved in efficiency, appearance, and cost. Advances in cell design, materials, and manufacturing have moved many commercial panels into the mid-teens to mid-20% efficiency band, with top models achieving low- to mid-20s percent conversion under standard test conditions.

| AspectImpactDetails | ||

| Savings | Financial Benefit | Properly sized systems can reduce household electricity bills significantly (typical estimates vary by region; some homes see reductions near 20%–30% or more depending on solar resource, system size, net metering, and storage). |

| Value Increase | Property Market | Homes with well-installed solar systems generally command higher resale values; exact increases depend on local market conditions and system ownership (owned vs leased). |

| Efficiency | Performance | Ongoing improvements—PERC, bifacial modules, and improved cell architectures—raise module efficiency and energy yield per roof area. |

| Climate Impact | Environmental Gain | By offsetting grid electricity generated from fossil fuels, solar power reduces carbon emissions per kWh produced. |

Common inverter choices include microinverters (one per panel), string inverters (one per string of panels), and hybrid/storage-capable inverters. Microinverters improve panel-level performance monitoring and can reduce losses from shading, while string inverters are generally lower cost at scale. When assessing a system, consider inverter conversion efficiency, warranty length, and whether the inverter supports battery storage.

To estimate how a specific system will perform where you live, use a solar production calculator or consult a local installer — these tools account for sunlight, panel and inverter specs, roof orientation, and shading to produce a realistic projection of electricity generation and potential savings.

Benefits of Solar Power for the Environment and Economy

Solar energy is a cornerstone of renewable energy strategies because it simultaneously reduces pollution and supports economic activity. Deploying solar power cuts greenhouse gas emissions compared with fossil-fuel generation and creates local work opportunities in manufacturing, installation, and maintenance (see resources such as IRENA and the IEA for regional data).

Contributions to Climate Change Mitigation

By displacing electricity from coal and natural gas plants, solar power reduces CO2 emissions per kWh delivered and lowers emissions of air pollutants. Compared with many thermal power plants, PV systems also require far less water for operation, which helps conserve freshwater resources in water‑stressed areas.

Economic Growth Through Green Jobs and Energy Security

The expanding solar industry supports jobs across the value chain—from panel manufacturing and project development to rooftop installation and system maintenance—helping local economies and workforce development. Solar also improves energy security by diversifying supply and reducing dependence on imported fuels, which can stabilize energy costs for communities and businesses.

Below are quick, illustrative indicators (figures vary by country and source):

- Employment: solar-related roles include installers, engineers, project managers, and manufacturing technicians—job growth tends to track deployment rates and supportive policy.

- Water savings: PV operation uses minimal water compared with conventional thermal plants that need cooling water.

- Local economic impact: rooftop and community solar projects keep investment and spending within local supply chains.

For homeowners and businesses considering solar, check local incentives, net-metering rules, and calculators that estimate emissions avoided and jobs supported by a given installation—these tools make the environmental and economic benefits concrete and actionable.

Innovations Leading the Future of Solar Technology

Rapid advances in solar technology and materials are improving energy yield, lowering costs, and widening applications—from rooftop systems on homes to large-scale projects powering cities. These innovations make solar energy technologies more effective for different users: homeowners, commercial operators, and utilities.

The Role of Bifacial Solar Panels and Thin-Film Cells

Bifacial solar panels capture sunlight on both the front and rear faces, increasing energy output per installed area—especially on reflective surfaces such as light-colored rooftops or ground-mounted arrays with high albedo. That added yield makes bifacial modules attractive where roof or land area is limited. Thin-film cells trade some efficiency for lower weight, flexibility, and potentially lower manufacturing cost; they work well in building‑integrated photovoltaics (BIPV) and curved surfaces where glass panels are impractical.

Practical takeaway: for tightly spaced installations or rooftop systems where every watt per square foot matters, bifacial modules can boost annual production; for architectural integration or lightweight applications, thin-film can be a good fit.

Advancements in Solar Energy Battery Storage

Battery storage is the critical companion to solar systems for increasing self-consumption and providing backup power. Modern lithium‑ion chemistries (including LFP) dominate residential and commercial storage because of high energy density and declining costs; flow batteries and other chemistries are maturing for long‑duration applications at utility scale. Storage lets systems shift solar generation to evenings, reduce peak demand charges, and improve grid resilience.

Examples: a small home system with a 10 kWh battery can cover evening loads for several hours after sunset, while larger commercial or community storage projects smooth demand and provide ancillary services to the grid.

| InnovationPrimary BenefitBest Fit | ||

| Bifacial modules | Higher energy yield per area | Ground mounts, reflective roofs, limited-area sites |

| Thin-film PV | Lightweight, flexible, aesthetic integration | BIPV, curved surfaces, low-weight applications |

| Battery storage (Li-ion, flow) | Time-shifting, backup, grid services | Residential backup, commercial peak shaving, utility-scale duration |

Global deployment continues to grow: innovators are combining these technologies—for example, bifacial panels with dedicated storage on commercial rooftops or thin-film BIPV on façade retrofit projects. When evaluating systems, consider specific energy goals (maximizing production, minimizing footprint, adding resilience) and compare technologies by lifetime energy yield, costs, and maintenance needs.

Want to explore which innovation fits your project? Start with a technology checklist: your available area, desired energy fraction to cover, budget, and whether you need storage or aesthetic integration. Then consult a local installer or system designer to translate those constraints into an optimal configuration.

Examining the Longevity and Impact of Solar Energy

Assessing the solar energy long-term impact shows that modern PV systems provide durable, low‑maintenance energy over decades. Properly specified and installed systems deliver steady energy output, reduce lifetime emissions, and typically require less ongoing input (water, fuel, or frequent parts replacement) than many conventional generators.

High-quality panels from manufacturers such as SunPower, REC, Panasonic, Maxeon, and Jinko are generally rated for 25–30 years of useful service. Degradation rates vary by technology and conditions; many manufacturers guarantee production on the order of 80%–90% of nameplate output over 10–25 years. Typical observed annual degradation for modern commercial panels is in the range of about 0.3%–0.8% per year depending on panel type and environment.

| Warranty/PeriodCommon Guaranteed OutputNotes | ||

| 0–10 years | ≈90%–97% | Early-life warranty and product defects covered by product warranty |

| 11–25 years | ≈80%–90% | Performance warranty often specifies minimum % output at year 25 |

| 25+ years | Varies | Panels typically continue producing power beyond warranty life at reduced output |

Panel warranties typically include a product (manufacturing) warranty and a performance warranty. Product warranties often cover defects for 10–15 years, while performance warranties guarantee a minimum power output for 25 years (terms differ by brand and model—check specific warranty documents).

- Monocrystalline panels often demonstrate slightly lower degradation rates (commonly toward the low end of the 0.3%–0.6% range).

- Severe weather and soiling can reduce short‑term output, but robust mounting, quality materials, and professional installation mitigate many risks.

- Annual or biannual inspections and basic cleaning extend system life and ensure warranties remain valid—most homeowners rely on a yearly check.

In summary, a well‑designed solar system offers multi‑decade energy generation with predictable decline in output and modest maintenance needs. When comparing systems, evaluate the combination of expected energy yield over the system lifetime, warranty coverage, and local environmental factors (sunlight, temperature, and soiling) to estimate total energy produced and cost per kWh over the system’s useful life.

The Pioneering Perovskite Solar Cells and Their Features

Perovskite solar cells are an important emerging class of photovoltaic technology known for rapid improvements in laboratory efficiency and potentially lower manufacturing costs. They are a promising part of the next wave of solar energy breakthroughs, but it’s important to separate lab records from commercial readiness.

High Efficiency and Low-Cost Manufacturing

Perovskite solar cells have progressed quickly in lab settings: early reports showed single-digit efficiencies a decade ago, while recent research cells have exceeded the high‑20s to low‑30s percent range under laboratory conditions. These gains stem from perovskites’ strong light absorption and favorable charge‑transport properties.

Manufacturing approaches such as solution processing, printing, and vapor deposition can be less capital‑intensive than some silicon processes, which suggests potential for lower costs at scale. However, most high‑efficiency perovskite results are still at pilot or lab scale, and commercialization requires addressing stability, encapsulation, and scaling challenges.

Flexibility of Application in Solar Solutions

Perovskite solar cells offer design flexibility: they can be produced on lightweight substrates and patterned or colored for building‑integrated photovoltaics (BIPV). Tandem devices that stack perovskite cells over silicon are showing particular promise because they can push efficiencies beyond single‑junction silicon limits.

Researchers are also exploring niche applications—lightweight modules for portable electronics or wearables—where perovskites’ low weight and potential low-cost manufacturing matter most.

Stability remains the primary technical hurdle. Perovskite materials can be sensitive to moisture, UV, and thermal stress; current research focuses on encapsulation techniques, compositional engineering, and lead‑free formulations to improve longevity and environmental safety. Claims of multi‑decade lifetimes are optimistic at present and depend on successful advances in these areas.

| YearRepresentative lab efficiency start (%)Representative lab efficiency now (%)Commercial outlook | |||

| ~2009 | Low single digits | ~25–30 (lab progress over decade) | Research → pilot production; commercial scale-up in progress |

| 2017 | ~20 (early rapid gains) | ~25–33 (records in labs) | Tandems and niche BIPV trials advancing |

| 2021 | Varied | High 20s in labs | Work on lead alternatives and stability ongoing |

In short, perovskite solar cells are a highly promising technology for improving overall solar energy conversion and enabling new applications worldwide, but their long‑term field durability and full commercial deployment depend on resolving stability and environmental concerns. Watch for pilot projects and industrial demonstrations as the next step toward broader adoption.

Integration of AI in Solar Technology Development

The solar power industry is evolving rapidly with the help of artificial intelligence. AI systems analyze large datasets—satellite imagery, weather forecasts, panel telemetry, and grid signals—to optimize generation, reduce downtime, and improve long‑term performance of solar energy systems.

Practical AI applications include predictive maintenance that identifies failing components before they cause outages, real‑time adjustments to inverter settings or tracker angles based on clouds and irradiance, and short‑term forecasting of solar generation to support grid balancing. These capabilities boost energy yield, extend equipment life, and reduce operating costs for owners and utilities.

Public and private funding is accelerating these efforts; for example, government grants and industry R&D programs have supported multi‑million dollar projects that combine AI with solar operations to enhance forecasting and grid reliability (check specific program announcements for exact award amounts and recipients in your region).

| DevelopmentImpact | |

| AI-driven predictive maintenance | Reduces operational costs and prolongs system life by detecting faults early through pattern detection on telemetry data |

| Real-time adjustments in panel positioning and inverter settings | Increases energy output by adapting to environmental changes and reducing mismatch losses |

| Short-term generation and net-load forecasting | Enhances grid stability and reliability by improving dispatch and storage scheduling |

Government support—through tax incentives, pilot programs, and research funding—helps scale AI-enabled solutions by lowering technology risk for utilities and developers. For project owners, consider AI‑enabled monitoring or O&M services if you want improved uptime and finer-grained production insights; several vendors now offer subscription services that bring these analytics to residential and commercial systems.

Overall, integrating AI into solar systems strengthens the value proposition of solar energy by increasing effective output, reducing avoidable downtime, and enabling better alignment between distributed solar generation and grid needs.

Addressing the Limitations of Current Solar Technology

Solar energy is a powerful tool in the shift away from fossil fuels, but current solar technology has practical limits that planners, manufacturers, and policymakers must address. Below we separate the main challenges and outline mitigation pathways so readers can understand trade‑offs and solutions.

Performance variability and resource limits

Solar output depends on sunlight and local weather: cloudy conditions, high latitudes, and seasonal changes reduce instantaneous generation and make supply less predictable than dispatchable sources like natural gas plants. Mitigations include geographic diversification, hybrid systems (solar + storage or solar + gas peaker backup), and improved forecasting to integrate variable production into the grid more smoothly.

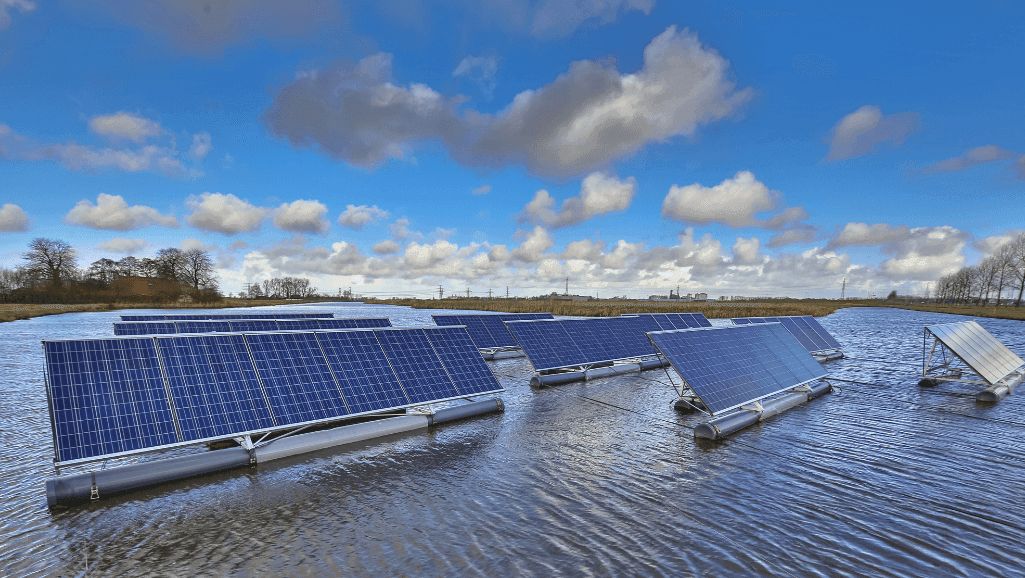

Land use and integration in built areas

Utility‑scale projects require area for panels, and land availability can be a constraint—especially near population centers. Urban deployments may also face aesthetic or zoning barriers. Solutions include rooftop and building‑integrated photovoltaics (BIPV), agrivoltaics that combine farming and PV, and using brownfields or low‑value land to reduce competition with other uses.

Upfront cost and storage requirements

Initial system costs—particularly for inverters and batteries—remain a barrier for some adopters. While prices have fallen, adding reliable battery storage increases capital expenditure. Policy incentives, low‑cost financing, and continued declines in battery and inverter costs help lower these barriers. For many installations, hybrid approaches (partial storage, time-of-use optimization) provide cost-effective resilience.

Materials, manufacturing impacts, and end‑of‑life handling

Manufacturing and disposal raise environmental concerns: certain thin‑film chemistries contain cadmium, and some cells use lead in small amounts. Proper recycling, take‑back programs, and developing lead‑free or less-toxic formulations can mitigate risks. Life‑cycle analyses generally show PV systems produce far fewer lifecycle emissions than fossil fuel plants, but responsible material sourcing and waste management remain essential.

- Address hazardous waste through recycling standards and manufacturer take‑back programs.

- Improve aesthetics (BIPV, low‑profile racking) to increase consumer acceptance in urban areas.

- Invest in energy storage research and grid upgrades to reduce reliance on fossil fuel peaker plants and ensure long‑term stability.

Examples of mitigation in practice: some cities incentivize rooftop and façade PV to avoid new land use; agrivoltaic pilots combine crops with panels to increase land productivity; and emerging recycling initiatives recover valuable silicon, glass, and metals from retired modules.

Summary: while solar technology limitations exist, a combination of design choices (bifacial modules, rooftop/BIPV, agrivoltaics), policy mechanisms (incentives, recycling mandates), and complementary technologies (storage, flexible grid resources, occasional natural gas backup) can greatly reduce constraints and help solar scale sustainably across diverse areas.

| StatisticData | |

| Total investment in Bhadla Solar Park, India | $1.4 billion (reported figure; verify source for project phase) |

| Area of Bhadla Solar Park | Approximately 10,000 acres (varies by reporting) |

| Installed capacity of Bhadla Solar Park | ~2,245 megawatts (aggregate figure reported for the park) |

| Installed capacity of Solar Star park, US | 579 MW (combined capacity reported) |

| Global daily solar energy potential | Illustrative estimates of solar irradiance are extremely large (figures such as “173,000 terawatts” are used illustratively—compare irradiance to demand with care and note unit/context) |

The Reduction of Solar Power Costs Through Technological Advancements

Over the past decades, technological progress and scale have driven down the effective cost of solar power, making solar energy an increasingly affordable option for homes, businesses, and utilities. Improvements in cell design, materials, and automated manufacturing have all contributed to lower module prices and reduced installed system costs.

Unlocking Economic Potential with Improved Solar Solutions

Lower component and balance‑of‑system costs have expanded where and how solar PV is deployed, unlocking economic opportunities across sectors. As manufacturing techniques and supply chains mature, developers can build projects at larger scale and lower unit cost, while homeowners benefit from more competitive system pricing and financing options.

Improvements in material science (for example, more efficient cell architectures) and manufacturing (automation, thinner wafers, higher throughput) have reduced the price per watt of PV modules and lowered the levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) for many solar projects.

To keep terms clear: historical “cost per watt” figures can refer to module spot prices, cell manufacturing cost, or total installed system cost—each uses different units and contexts. Below is an illustrative summary showing the long‑run trend (note: numbers vary by source and definition):

| Year / EraRepresentative trend | |

| 1970s | Early PV module prices were extremely high (order of hundreds of $/W for small volumes) |

| 2010s–2012 | Rapid price declines; module prices dropped to a few dollars per watt and below as manufacturing scaled |

| 2020s–2024 | Further declines in module and system costs; installed system prices vary by region but LCOE for utility PV and many rooftop systems became competitive with conventional generation in many markets |

Implications for Global Renewable Energy Adoption

Falling costs and improving performance have helped countries at many income levels adopt solar power. Policy support—subsidies, tax incentives, competitive auctions—and economies of scale have accelerated deployment. The International Energy Agency and other bodies project solar to be among the lowest‑cost sources of new electricity supply in many regions by the end of this decade, assuming continued technology improvements and supportive policy.

For project developers and consumers, the practical takeaway is to compare costs using consistent metrics (module price vs installed system price vs LCOE) and to track regional incentives and supply chain conditions. For U.S. projects, variations in state incentives and local labor costs can materially affect installed system prices and payback times.

If you’re considering solar, use up‑to‑date module price trackers or installer quotes in your area to get realistic numbers—those localized quotes will reflect current module costs, inverter prices, permitting, and available incentives that determine final system economics.

Principles of Energy Conversion in Perovskite Solar Cells

Energy conversion solar cells—notably perovskites—are a rapidly developing class of photovoltaic technology. Their strong light absorption and efficient charge transport pathways enable high laboratory efficiencies and make them an important area of research among emerging energy technologies.

At a high level, perovskite cells operate via the same basic process as other photovoltaics: photons are absorbed to form electron‑hole pairs, charges are separated and transported to electrodes, and an external circuit carries current. Perovskite materials show favorable photoluminescence properties that researchers use to diagnose recombination losses and improve charge extraction.

The Science Behind Photoluminescence and Charge Transport

Photoluminescence in perovskites is the emission of light after the material absorbs photons; measuring it helps scientists evaluate non‑radiative losses and material quality. Perovskite compounds often exhibit long carrier lifetimes and high mobilities that reduce recombination and improve the photogenerated current — key reasons for their rapid efficiency gains in the lab.

| Comparison ParameterSilicon Solar CellsPerovskite Solar Cells | ||

| Typical market role | Mature, dominant in commercial PV | Emerging; strong lab results, pilot manufacturing |

| Practical lifespan | 25+ years with >80% output commonly guaranteed | Stability improving; long‑term field data limited—protective encapsulation is critical |

| Efficiency (representative) | Real-world modules ~15%–22% | Lab devices >25% (commercial modules behind lab records) |

| Manufacturing approach | Large-scale silicon fabs; mature supply chains | Potentially lower-capex techniques (solution processing, printing) under development |

| Stability challenges | High stability and durability in field deployments | Requires further enhancements against moisture, heat, and UV for broad deployment |

Note: lab efficiency records for perovskite cells demonstrate potential but differ from commercial performance. When reading reported efficiency figures, always check whether the value is a laboratory record or for a commercially produced module.

Glossary (brief): photoluminescence — light re‑emitted by a material after excitation; electron‑hole pair — the paired charge carriers generated when a photon excites an electron; charge transport — movement of electrons/holes to contacts to produce current.

Understanding Solar Solution Components and Functionality

The world of solar power includes several specialized components that work together to convert sunlight into usable electricity. Knowing the role of each part helps homeowners, installers, and businesses design systems that meet performance, budget, and resilience goals using photovoltaic technology.

Key Components: Photovoltaics, DC, AC, and Inverter Technology

Photovoltaic (PV) panels contain cells that convert sunlight into direct current (DC) electricity. An inverter converts DC into alternating current (AC) for household appliances and grid export. Modern inverters also provide monitoring, safety shutdowns, and sometimes battery management functionality.

Common inverter options:

- Microinverters (e.g., Enphase IQ7): mounted at each panel, they optimize and monitor panel‑level output and reduce shading losses; they typically carry long warranties but raise system component count and upfront cost.

- String inverters: connect multiple panels in series; they are cost‑effective for uniform arrays but are more affected by shading or panel mismatch and often have shorter warranty periods (typical 5–15 years).

- Hybrid or storage‑ready inverters (e.g., Sol‑Ark style systems): integrate PV, battery charge/discharge control, and backup functions—useful when you want on‑site storage or intentional islanding capability.

Maximizing Efficiency with Smart Energy Management

Smart energy management systems monitor production and consumption and can automatically shift usage to align with solar generation or control battery charging. Key elements to consider include a battery management system (BMS) for safety, an energy management controller for scheduling loads, and an app or portal for system visibility.

Practical trade-offs to weigh when choosing components:

| ChoiceProsCons | ||

| Microinverters | Panel-level MPPT, better shading tolerance, granular monitoring | Higher upfront cost per watt, more electronics on the roof |

| String inverters | Lower cost for uniform arrays, simpler maintenance | Performance affected by weakest panel in string, less panel-level visibility |

| Hybrid inverters + battery | Enables storage, resilience, peak shaving | Higher capital cost, depends on battery chemistry (LFP, Li‑ion) and BMS quality |

Typical warranties and component lifespan (general guidance—check manufacturer specs):

| ComponentTypical Warranty | |

| Monocrystalline PV panels | ~25 years performance warranty |

| Microinverters (e.g., Enphase IQ7) | Often 20–25 years (model dependent) |

| String inverters | 5–15 years typical |

| Hybrid inverters | Varies—check vendor for storage integration terms |

Simple homeowner checklist to choose system components:

- Define your goals: maximize production, minimize cost, add backup, or enable monitoring.

- Assess your roof: orientation, shading, and available area determine panel count and type.

- Decide on storage: battery sizing depends on desired hours of backup or self‑consumption targets.

- Compare warranties and expected lifetime energy yield (kWh) rather than only upfront price.

- Ask about monitoring and O&M options—remote monitoring can identify issues quickly and improve long‑term performance.

To learn more about how these components interact and what fits your situation, consult reputable guides or request quotes from local installers who can provide tailored system designs and up‑to‑date pricing.

For additional background reading, see resources such as the National Grid’s solar power guide.

Exploring Various Solar Solution Types for Energy Needs

Solar solutions vary by scale and purpose—ranging from small rooftop arrays on homes to large utility projects powering cities. Choosing the right type depends on your energy goals (reduce bills, increase resilience, or lower emissions), available area, and budget.

Home and Commercial Applications

Home systems commonly come as grid‑tied or off‑grid configurations. Grid‑tied systems connect to the utility and are often the most cost‑effective option; they can offset a portion of household energy use (the exact share depends on system size, roof area, and local sunlight). Off‑grid systems combine panels with batteries and sometimes backup generators for complete independence—best for remote areas or where grid reliability is poor.

Commercial and industrial projects scale these principles up: rooftop or carport PV on buildings reduces operating costs and emissions, while ground‑mounted arrays or solar farms supply utility‑scale power. Commercial projects often pair solar with storage and energy management to shave peak demand charges and improve energy security.

Advancements in Solar Technology Accessibility

Improved manufacturing, financing, and modular system designs have made solar systems more accessible worldwide. Hybrid systems (PV + storage) and standardized, lower‑cost panels help broaden deployment across diverse projects—from small residential installs to community and large commercial arrays. Many countries deploy tailored incentive programs and project auctions to accelerate adoption at scale.

Quick example comparison: a modest 6 kW home rooftop system in a sunny U.S. state may reach payback in 6–10 years after incentives, while a commercial rooftop (hundreds of kW) can see faster returns due to larger scale and different tariff structures—local installers and calculators provide region‑specific estimates.

If you’re evaluating options, start with a simple checklist: available roof or land area, estimated annual sunlight, your budget and financing options, and whether you want backup power. Then request quotes from local installers to get tailored system designs and projected savings.

Conclusion

Solar energy has moved from niche technology to a mainstream source of clean power. Capturing sunlight and converting it into electricity and heat provides a practical path to reduce emissions, increase local energy resilience, and diversify the global energy mix. While illustrations such as “one hour of sunlight equals a year’s worth of global energy” help communicate the sun’s enormous potential, remember these are high‑level comparisons that depend on collection area and conversion efficiency.

Declining costs and growing investment have accelerated deployment: module and system prices have fallen dramatically over recent decades due to improvements in materials, manufacturing, and scale (see IEA and industry trackers for up‑to‑date figures). Large investment flows—public and private—are supporting projects worldwide and creating jobs across the supply chain. These trends make solar power an increasingly affordable, large‑scale option for homes, businesses, and power plants.

Looking ahead, new technologies—perovskite tandems, multi‑junction cells, and improved storage—may further lower costs and raise efficiency, broadening where and how solar systems are deployed. As adoption expands, solar is expected to supply a growing share of electricity in the United States and around the world, contributing to climate goals while supporting economic activity.