Solar power vs solar energy is an important distinction for homeowners, businesses and policymakers. Solar energy is the raw energy from the sun — sunlight and its heat — while solar power is the electricity produced when we capture that energy with solar panels and convert it into usable electricity. Understanding the term and the practical difference helps you choose the right system and estimate costs and benefits for your home.

The sun produces an enormous amount of energy. For context, scientists note the sun generates vast quantities of radiative energy each second; commonly cited summaries suggest a short period of global sunlight (often phrased as roughly an hour to 90 minutes of full sunlight, depending on assumptions) could meet annual human energy needs — confirm the calculation source when publishing. Advances in solar panel technology and falling costs have made solar power far more accessible for homes and businesses in recent times.

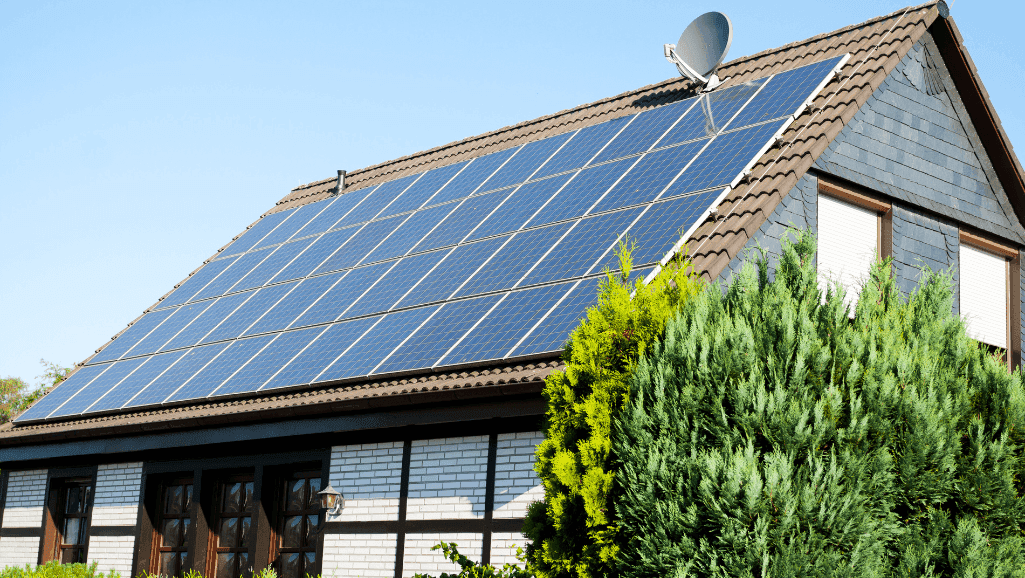

A typical residential solar system in Canada often ranges from roughly a 4 kW to 8 kW installation — commonly 15 to 25 panels depending on panel wattage — and individual modules contain multiple cells (many modern panels use between 60 and 120 cells, though configurations vary). Panels and inverters work together to turn solar energy into the electricity your home uses. Federal and provincial grants, rebates and low-interest loans in Canada further lower the upfront cost of going solar.

Going solar reduces reliance on coal and natural gas and lowers household carbon emissions. In many Canadian markets, with incentives and current electricity rates, simple payback for a typical home system is often quoted in the 5 to 7 year range — actual payback depends on system size, local sunlight, net‑metering or export rules, and available rebates, so get a local estimate. If you’re a homeowner, read the overview below to decide whether going solar is right for you.

Key Takeaways

- Solar energy = the sun’s raw energy (sunlight and heat); solar power = the electricity we generate from that energy using solar panels.

- Sunlight contains a tremendous amount of energy; some summaries estimate a short global-sunlight period could meet yearly needs — verify the source before citing.

- A typical home system commonly uses about 15–25 panels (panel cell counts and wattages vary); panels plus inverters convert solar energy into usable electricity.

- Canadian federal and provincial programs (rebates, grants, loans) improve the economics of going solar — check local programs to see available incentives.

- When incentives, system size and electricity rates align, simple payback is often quoted around 5–7 years; actual results vary by location and system.

Understanding the Basics of Solar Power and Solar Energy

Start by separating power and energy: power (kilowatts, kW) is the rate at which a system produces or uses energy at a moment in time; energy (kilowatt-hours, kWh) is the total amount used over a period. Simple example: a 5 kW solar system operating at peak for one hour produces 5 kWh of electricity (5 kW × 1 hour = 5 kWh).

Defining Power and Energy

These definitions explain how solar panels convert sunlight into usable energy. The photovoltaic effect — first observed in the 1800s and commercialised for silicon PV cells (a landmark in 1954 at Bell Labs) — is the physical basis for PV electricity. PV modules produce instantaneous power (kW) and, across a day or year, generate energy measured in kWh.

Remember: solar PV panels generate electricity while solar thermal systems capture heat. A panel’s power rating depends on its size and efficiency and on how much sunlight it receives; total energy produced equals that rated power multiplied by the operating time at that power level.

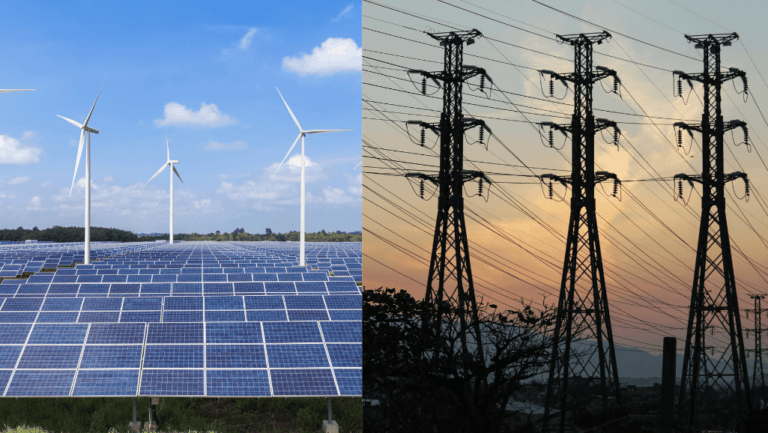

The Role of Solar Power and Solar Energy in Sustainable Living

Adopting solar energy reduces reliance on fossil fuels and lowers household carbon footprints, helping to address climate change. Improvements in solar technology and falling equipment costs have made it easier for homeowners and businesses to adopt solar power, cutting energy bills and emissions.

| CountrySolar Power Capacity (GW) | |

| China | 253.4 |

| United States | 73.8 |

| Japan | 67.0 |

| Germany | 53.8 |

| India | 42.8 |

Table note: these figures illustrate major national capacities — confirm the year and source (for example, IRENA or IEA) before publishing. As costs fall and energy solar power deployments expand, both rooftop systems and utility-scale projects will play larger roles in a cleaner energy mix.

What is Solar Power?

Solar power is the process of turning sunlight into electricity using photovoltaic (PV) cells inside solar panels. Solar PV systems — from small rooftop arrays to large utility plants — let homes, businesses and communities generate clean electricity at the point of use and reduce transmission losses.

The Photovoltaic Effect: Harnessing Sunlight for Electricity

The photovoltaic effect (observed in the 19th century and commercialised for silicon PV cells with a landmark in 1954 at Bell Labs) is the scientific basis for solar power: photons from the sun free electrons in silicon to create a current. Improvements in PV manufacturing and balance-of-system components have driven large cost reductions over recent decades (check IRENA/IEA for the latest percentage changes).

Solar power produces instantaneous power (kW) and, over hours or a year, produces energy (kWh). Plenty of sunlight reaches Earth — some summaries estimate an hour to 90 minutes of global sunlight could supply humanity’s annual energy needs depending on assumptions — making solar an abundant energy source across scales.

Applications of Solar Power in Daily Life

Solar power is versatile: rooftop residential panels, commercial arrays, community solar and large solar farms all deliver electricity. Paired with storage (solar-plus-storage), systems can supply power when the sun is down. Common uses include off-grid pumps, rooftop installations on Ontario homes, and utility-scale plants that feed provincial grids.

| Type of Solar Panel SystemDescription | |

| Residential Solar | Rooftop PV systems sized for homes (common in Canadian provinces with rebate programs) |

| Commercial Solar | Systems on businesses and institutions to lower electricity bills |

| Utility-Scale Solar | Large solar power plants that provide grid-scale electricity |

| Community Solar | Shared installations enabling access to solar for renters or shaded properties |

| Solar-Plus-Storage Systems | PV systems paired with batteries to provide electricity when sunlight is unavailable |

Real benefits of solar power include lower electricity bills, reduced greenhouse-gas emissions and improved local resilience. For Canadians considering an installation, compare rooftop and community options and request a local estimate to see how a PV system would perform for your property. A quick checklist: estimate your roof’s usable area, check local sun rays and orientation, and ask installers for expected annual production and payback time.

What is Solar Energy?

Solar energy is the full range of energy we receive from the sun — including visible sunlight, heat and the radiant energy that drives weather, climate and photosynthesis. It isn’t limited to electricity: solar energy supplies warmth, daylight and the primary energy that sustains ecosystems.

Solar thermal systems capture sunlight as heat rather than converting it to electricity. That heat can warm domestic water, provide space heating, or supply process heat for industry. In many applications, solar thermal is an efficient, low‑carbon alternative to fossil‑fuel heating and can be cheaper over time depending on fuel prices and incentives.

Solar energy is intermittent — available when the sun shines — and output varies by season and location. Storage (batteries for PV or thermal tanks for heat), hybrid systems and smart controls help manage intermittency and improve system uptime. Falling equipment costs and better controls have made energy‑solar projects more viable in recent years.

To put growth in context, global solar PV capacity expanded rapidly during the 2010s (for example, reported capacity rose from tens of gigawatts in 2010 to several hundred gigawatts by 2020 — confirm latest IRENA/IEA figures before publishing). That rise shows the increasing role of solar energy and solar PV in the global energy mix.

Pros and cons at a glance:

- Pros: abundant sunlight, low operating emissions, scalable from small systems to utility farms, and falling costs that improve payback.

- Cons: variability (day/night, weather, seasons), upfront capital required, and site‑specific performance that depends on roof area, orientation and local sunlight.

Decision checklist for homeowners: estimate your roof’s usable area and likely annual production, compare a solar‑thermal hot‑water system versus a PV + electric water heater using local fuel prices and incentives, and request a site‑specific estimate from a certified installer. For Canadian projects, consult provincial rebate pages and confirm local suitability before committing to a design or purchase.

Solar Thermal Systems: Capturing the Sun’s Heat

Solar thermal systems capture sunlight as heat rather than converting it to electricity. They commonly use solar collectors — flat‑plate, evacuated‑tube or concentrating collectors — to warm a fluid (water or air) that transfers heat to where it’s needed. Solar thermal is a low‑carbon way to provide domestic hot water, space heating or industrial process heat.

Solar Water Heaters: Reducing Energy Bills and Conventional Heating Reliance

Solar water heaters are one of the most common solar‑thermal uses. Collectors heat water that is stored in an insulated tank for later use, reducing the need for electricity or natural gas for hot water. Active systems use pumps to circulate fluid; passive systems rely on natural convection. The best choice depends on climate, roof area and hot‑water demand.

Typical performance and longevity vary by design: low‑temperature collectors commonly convert about 20–40% of incoming solar energy, medium‑temperature systems 40–60%, and concentrating systems (CSP) can reach significantly higher thermal efficiency. Well‑maintained collectors and associated equipment often last around 20–25 years — check manufacturer specs and warranties when comparing options.

| System TypeEfficiencyLifespan | ||

| Low‑temperature solar thermal | 20% to 40% | 20–25 years |

| Medium‑temperature solar thermal | 40% to 60% | 20–25 years |

| High‑temperature solar thermal (CSP) | Up to 80% or more | 20–25 years |

Industrial Applications of Solar Thermal Energy

Solar thermal scales from household hot‑water systems to industrial process heat and large CSP plants that concentrate sunlight to generate steam for turbines. When paired with thermal energy storage (molten salts, insulated hot‑water tanks or other media), CSP can provide dispatchable power — helping to smooth variability and, in some cases, displace fossil‑fuel plants.

Thermal storage is central: it stores excess heat from sunny periods for use during cloudy periods or overnight, increasing usable energy and improving economics. Estimates that describe the abundance of solar energy (for example, phrases like minutes to hours of global sunlight equating to a year’s energy needs) illustrate the huge potential of the sun — verify the exact source and assumptions before citing.

Where solar thermal performs best: regions with steady solar radiation and significant hot‑water or process‑heat demand. In Canada, compare a solar‑thermal hot‑water installation against a PV + electric water‑heater setup by evaluating local sunlight, fuel prices and provincial incentives. Request a site‑specific estimate from a local contractor to calculate likely savings, payback and suitable system size.

The Greenhouse Effect and Solar Energy’s Role in Sustaining Life

Solar energy powers Earth’s climate system and makes life possible. Roughly 30% of incoming solar radiation is reflected back to space while the remaining ~70% is absorbed by the atmosphere, oceans and land, warming the planet. That absorbed energy is later emitted as infrared; greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide and water vapour trap some of that heat, creating the natural greenhouse effect that keeps the Earth’s temperature suitable for life (see NASA and IPCC summaries for details).

The greenhouse effect is essential — without it Earth would be far colder — but human activities (burning fossil fuels, land‑use change) have increased greenhouse‑gas concentrations and strengthened the effect, driving climate change and global warming.

How Solar Energy Maintains Earth’s Temperature

Longer‑term variations in incoming solar energy (Earth’s tilt, orbital cycles and solar output) influence climate on geological timescales, but the rapid warming observed today is primarily due to higher greenhouse‑gas levels. The atmosphere acts like a blanket: it admits sunlight but slows the loss of heat to space, keeping the global average near ~15°C (59°F).

The Importance of Greenhouse Gases in Trapping Heat

Greenhouse gases differ in how long they persist and how strongly they warm the planet. For example: methane (CH4) has an atmospheric lifetime of roughly 12 years and a 100‑year global warming potential (GWP) commonly cited around 28–36; nitrous oxide (N2O) lasts much longer (order of a century) with a GWP in the hundreds. Carbon dioxide (CO2) is the baseline (GWP = 1) but includes removal on both short and very long timescales — see IPCC for ranges and context.

| Greenhouse GasAtmospheric Lifetime (years)Global Warming Potential (100‑year) | ||

| Carbon Dioxide (CO2) | Years to centuries (complex removal) | 1 |

| Methane (CH4) | ~12 | 28–36 |

| Nitrous Oxide (N2O) | ~121 | 265–298 |

Linking this to energy: each kWh of low‑carbon solar power displaces fossil‑fuel electricity and prevents CO2 emissions. Example calculation: if your 5 kW residential PV system produces ~5,000 kWh/year and your local grid emits 0.4 kg CO2 per kWh, then the system avoids roughly 2,000 kg CO2/year (5,000 kWh × 0.4 kg CO2/kWh = 2,000 kg CO2) — use NRCan/IEA regional emission factors to refine this estimate. Typical 5 kW production in many Canadian locations is often reported in the ~5,000–6,000 kWh/year range (site dependent) — verify with local solar maps and installer estimates.

Understanding the greenhouse effect and solar energy’s role helps prioritise solutions: deploying more solar power and other renewables reduces emissions, improves resilience and contributes to long‑term climate stabilisation.

Photosynthesis: The Foundation of Life Powered by Solar Energy

Photosynthesis is the biological process that converts sunlight into chemical energy (carbohydrates). Plants, algae and photosynthetic bacteria (notably cyanobacteria) capture solar radiation and combine it with carbon dioxide to produce sugars and oxygen — the basic fuel for nearly all life.

Global photosynthesis is vast. Rough estimates indicate terrestrial and marine photosynthetic organisms convert on the order of 100–200 billion tonnes of carbon annually (methodologies vary; cite primary sources such as peer‑reviewed literature when publishing). Marine cyanobacteria and microscopic algae contribute a very large share of oceanic primary production, while land plants — including Canada’s boreal forests — store and cycle substantial carbon in biomass.

At the cellular level, leaf chloroplasts contain light‑absorbing pigments (chlorophyll) where the light reactions and carbon fixation occur. Each chloroplast functions like a tiny solar‑powered factory: photons excite electrons in pigment molecules, driving the chemical work that produces sugars and releases oxygen.

| Photosynthetic OrganismContribution to Global Photosynthesis | |

| Cyanobacteria | ~50% (marine contribution significant) |

| Land Plants | ~40% |

| Oceanic Algae | ~10% |

Why this matters: photosynthesis is the natural example of converting solar energy into usable chemical energy — a concept that informs renewable technologies and biomass strategies. For Canadians, protecting and managing forests (especially boreal regions) preserves major carbon sinks that help offset emissions and support biodiversity and ecosystem services.

Fossil Fuels: A Nonrenewable Legacy of Solar Energy

Fossil fuels — petroleum, natural gas and coal — powered industrial development for centuries. They are essentially stored, ancient solar energy: plants and microorganisms captured sunlight via photosynthesis millions of years ago, and under heat and pressure those remains transformed into the hydrocarbons we extract and burn today.

The Origins of Petroleum, Natural Gas, and Coal

Over geological time, accumulated organic matter (from marine plankton to swamp forests) was buried and altered into oil, gas and coal. In other words, fossil fuels concentrate solar energy from past eras and release it quickly when combusted.

Environmental Challenges Associated with Fossil Fuels

Burning fossil fuels releases large amounts of CO2 and other pollutants, increasing the greenhouse effect and harming air and water quality. That raises a household’s carbon footprint, contributes to higher global temperatures, sea‑level rise and more extreme weather.

| Fossil FuelEnvironmental Impact | |

| Petroleum | Oil spills, air pollution, greenhouse gas emissions |

| Natural Gas | Methane leaks, groundwater risks, greenhouse gas emissions |

| Coal | Air pollution, acid rain, land degradation, greenhouse gas emissions |

Typical carbon intensity for fossil‑fuel electricity varies by technology and region (often hundreds of grams CO2 per kWh for coal and lower for gas); by contrast, lifecycle emissions for solar power are a small fraction of those values — see IEA or NRCan for region‑specific factors. What homeowners can do today: improve home efficiency, switch to renewable electricity where available, and request a local estimate for a solar system to see potential emissions and cost savings.

Solar Power vs Solar Energy: Key Differences and Similarities

Solar power vs solar energy are related but distinct terms. Solar power refers specifically to the generation of electricity from sunlight (typically via photovoltaic cells and panels), while solar energy is the broader energy coming from the sun — including heat, light and the energy that sustains ecosystems. Knowing the difference helps homeowners, businesses and policymakers choose the right systems and policies.

Scope and Applications

At a glance:

| TermDefinition & Typical Uses | |

| Solar power | Electricity generated by PV systems and inverters for homes, businesses and utilities (rooftop PV, solar farms, solar‑plus‑storage). |

| Solar energy | All sun‑derived energy: solar thermal for hot water or district heating, photosynthesis that supports food chains, and radiant energy driving climate systems. |

Use‑cases: a rooftop PV array (solar power) cuts household electricity bills and grid demand; a solar‑thermal district heating system (solar energy) supplies space and water heating at scale.

Environmental Impact and Sustainability

Both solar power and broader solar‑energy uses reduce reliance on fossil fuels and lower greenhouse‑gas emissions. Solar technologies have relatively low lifecycle emissions, and pairing PV with batteries or thermal storage increases reliability. Investing in solar systems supports local jobs, reduces transmission losses and helps lower a household’s carbon footprint compared with fossil‑based electricity.

| Energy SourceGlobal Energy Production (2018) | |

| Fossil Fuels | 81% |

| Hydroelectricity and Other Renewables | 14% |

| Nuclear Energy | 5% |

Table note: this highlights fossil fuels’ dominance (source: IEA/World Energy Outlook — confirm year and update data as needed). Increasing deployment of solar power and other renewables is essential to shift the global energy mix, reduce emissions and build a cleaner energy future. For homeowners: compare PV and solar‑thermal options for your home, request a site estimate and check local incentives to see which solution delivers the best value.

The Environmental Benefits of Embracing Solar Technology

Solar technology is an effective way to cut greenhouse‑gas emissions and protect ecosystems. By generating low‑carbon electricity from the sun, solar power reduces reliance on fossil fuels and lowers the environmental impact of energy production — see lifecycle analyses for full context.

Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Air Pollution

Solar panels produce electricity without combustion, so they emit negligible air pollutants during operation. Replacing grid electricity supplied by fossil fuels with rooftop PV directly reduces a household’s carbon footprint. For example, a typical 5 kW residential PV system in many Canadian locations can produce roughly 5,000–6,000 kWh/year and may avoid about 1.5–2.0 tonnes CO2 annually compared with fossil‑dominated grid supply (actual savings depend on local grid emission factors — verify with NRCan or IEA).

Compared with conventional thermal power plants, solar installations also avoid many air contaminants produced by combustion and require less water during operation.

Mitigating Climate Change and Promoting a Cleaner Planet

Solar energy uses far less water than steam‑cycle thermal plants, easing pressure on local water resources. Industry efforts to reduce production impacts (for example, reductions in water use per MW reported by some manufacturers) are ongoing — confirm specific company claims and years before citing.

| YearWater Consumption per MWReduction | ||

| 2021 | 761 m³ | – |

| 2022 | 628 m³ | 17.5% |

Beyond environmental gains, solar panels give homeowners and businesses more control over their electricity costs. Generating on‑site power reduces grid dependency and, with favourable policies like net metering, can deliver meaningful money savings and lower monthly bill volatility over a system’s lifetime.

The solar industry also supports local jobs in manufacturing, sales, installation and maintenance — an economic benefit alongside environmental savings.

Action for homeowners: check federal and provincial rebate pages, then request a local estimate to calculate likely money savings and payback for your property. Get a free quote from a certified local installer to estimate annual energy production, expected savings and simple payback time.

Economic Advantages of Investing in Solar Power and Solar Energy

Investing in solar power and broader solar energy solutions can deliver clear financial benefits for homeowners, businesses and communities. On-site generation reduces reliance on the grid, lowers monthly bill volatility and — with favourable incentives — can produce meaningful long‑term money savings and a strong return on investment.

Example for a Canadian homeowner: a typical 5 kW residential system (a common size for many suburban home roofs) often produces about 4,000–6,000 kWh/year depending on location and orientation. At average provincial electricity rates, that production frequently translates into noticeable annual savings and a multi‑year payback; many Canadian analyses report simple paybacks of roughly 5–10 years when federal and provincial incentives are included (actual cost, payback and time to break even vary by province, system size and financing).

Businesses also benefit: larger commercial systems reduce operating energy costs and can deliver attractive ROI for energy‑intensive facilities while improving sustainability credentials. Financing options — including leases, loans and power purchase agreements (PPA) — plus tax incentives often improve project economics for commercial installations.

Governments influence payback materially through incentives, rebates and policies (for example, net metering or export credit programs). To estimate your specific payback, follow these steps:

- Estimate required system size for your home or facility (kW).

- Check your local electricity rate ($/kWh) and expected annual production (kWh/year).

- Apply federal/provincial rebates, tax credits and incentives to the upfront cost.

- Choose financing (cash, loan, lease, PPA) and calculate annual savings to determine payback and ROI.

| InvestmentTypical Annual SavingsEstimated Break‑Even | ||

| Residential solar system (example) | Varies by site (often thousands $/year) | 5–10 years (with incentives) |

| Commercial solar system | Business‑specific; can be tens to hundreds of thousands $/year | 4–10 years (project dependent) |

Beyond direct savings, solar systems can increase property value (homes with PV often command a premium), strengthen energy independence and support local job creation in manufacturing, sales and installation. If you’re considering an investment in solar technology, get a local estimate and use an interactive payback calculator to model scenarios — many Canadian installers and government sites offer free tools and site assessments to help homeowners decide.

Conclusion

Solar power vs solar energy are both essential to a cleaner energy future: solar energy refers to all energy from the sun (heat, light and the energy that sustains ecosystems), while solar power describes the production of electricity from sunlight (typically via PV systems). Advances in solar technology and falling costs are making both approaches more accessible to households and businesses.

Key takeaways:

- Solar energy supplies heat, light and the foundation for photosynthesis; solar power converts that energy into electricity for homes and industry.

- Deploying solar systems reduces reliance on fossil fuels, lowers emissions and delivers long‑term money savings for many homeowners and businesses.

For Canadian homeowners: get a local estimate to see how a solar system would perform for your home, and check federal and provincial rebate pages to understand available incentives (these significantly affect payback and money saved). Use authoritative sources (NRCan, IEA, IPCC) when comparing emissions and energy amounts.